Description

The Ford Zakspeed C100 was a purpose-built Group C prototype racer developed in the early 1980s, created during an era when Ford sought to reestablish itself in international sports car racing. Conceived as a successor to the Capri and Mustang-based touring cars that Zakspeed had successfully campaigned, the C100 represented a bold leap into endurance racing, aimed squarely at the FIA’s new Group C regulations that prioritized fuel efficiency as well as outright speed.

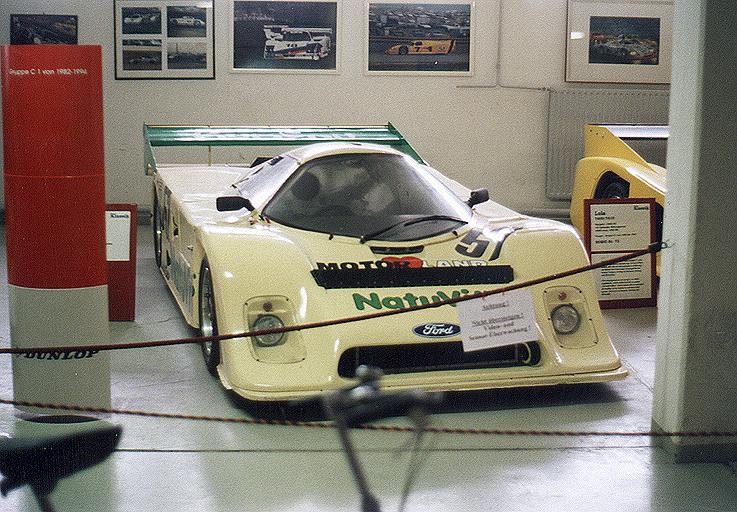

The car’s design was radical for its time. Built around a lightweight aluminum monocoque chassis with advanced aerodynamics, the C100 featured a wide, low-slung body with integrated ground-effect tunnels, large wheel arches, and a sharply pointed nose. Its wedge-shaped profile and massive rear wing reflected the cutting-edge thinking of early Group C design, where manufacturers were experimenting with airflow management to maximize downforce and minimize drag. The result was a futuristic machine that looked every bit as advanced as its competitors from Porsche, Lancia, and others.

Inside, the C100 was pure race car. The cockpit was stripped to the essentials, with a single racing seat, full harness, and a dashboard dominated by gauges and switches to monitor the engine and fuel consumption. Driver comfort was minimal, as the car was built for endurance racing performance rather than ease of operation. Its compact and claustrophobic cockpit emphasized efficiency and weight reduction.

The heart of the C100 was Ford’s Cosworth DFL engine, a development of the legendary DFV Formula 1 V8. Enlarged to 3.9 or 4.0 liters for endurance racing, the DFL was capable of producing around 530 to 600 horsepower, depending on tuning and configuration. Mated to a Hewland racing gearbox, the engine delivered both strong power and proven reliability, though it was often stretched to its limits in the grueling demands of Group C competition.

The Ford Zakspeed C100 made its debut in 1982, but its career was plagued by challenges. The car showed flashes of speed, occasionally qualifying competitively against the dominant Porsche 956s, but it struggled with reliability and development issues. Ford’s support for the program was inconsistent, and without the resources of larger manufacturers, the C100 was unable to reach its full potential. Zakspeed worked to refine the design, producing evolutions such as the C100B, but the results remained mixed, with only a handful of promising performances to show for the effort.

Despite its limited success on the track, the C100 remains a fascinating chapter in Ford’s racing history. It represented Ford’s ambition to return to the top tier of endurance racing, carrying forward the company’s legacy from the GT40 era into the new world of Group C. The partnership with Zakspeed highlighted the German outfit’s ingenuity and Ford’s willingness to experiment with advanced technologies, even if the program ultimately lacked the sustained investment needed to match Porsche’s dominance.

Today, the Ford Zakspeed C100 is remembered as a bold but flawed effort—an ambitious prototype that showed promise but never realized its potential. Surviving examples are rare and highly prized among collectors of Group C machinery, serving as reminders of Ford’s willingness to take risks in pursuit of racing glory. While it did not achieve the victories of the GT40, the C100 stands as a symbol of Ford’s ongoing pursuit of innovation and speed in the world of endurance racing.