Description

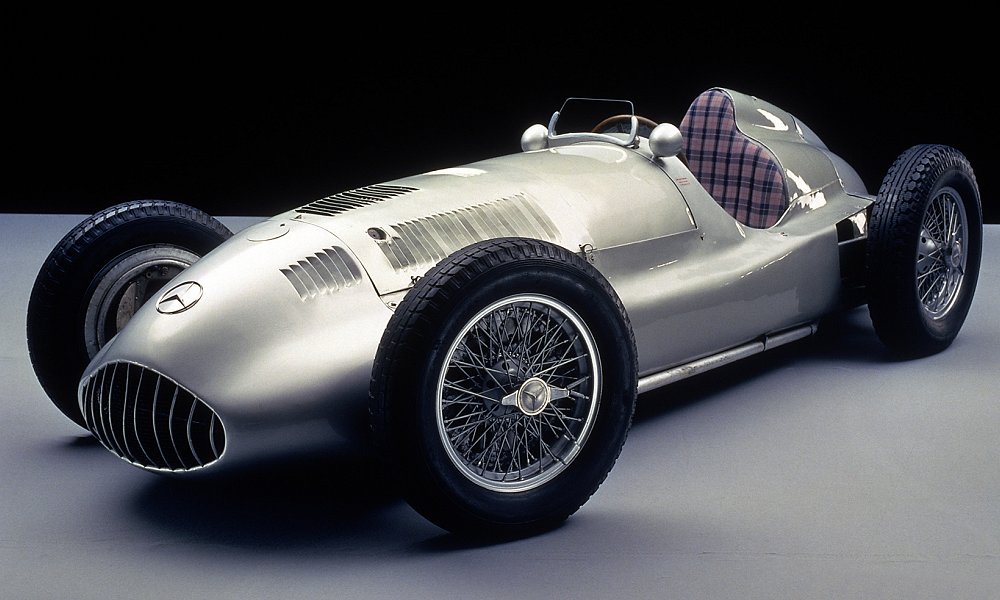

The Mercedes-Benz W165 1.5 Tripolis was a unique and highly specialised Grand Prix racing car, created as a rapid-response project to contest a single, strategically important event. Developed in extraordinary secrecy and speed for the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix, the W165 was Mercedes-Benz’s answer to new regulations that favoured small-capacity, supercharged engines. It stands as one of the most remarkable examples of focused engineering in motorsport history, designed, built and raced successfully in a matter of months.

The Tripoli Grand Prix was run to the voiturette regulations, which limited engine capacity to 1.5 litres with supercharging. These rules were intended to disadvantage the dominant German Grand Prix teams, whose large supercharged cars had overwhelmed competition under previous formulas. Rather than withdraw, Mercedes-Benz committed to designing a completely new car from scratch. The result was the W165, a compact, lightweight and immensely powerful machine that bore little resemblance mechanically to the company’s earlier Silver Arrows.

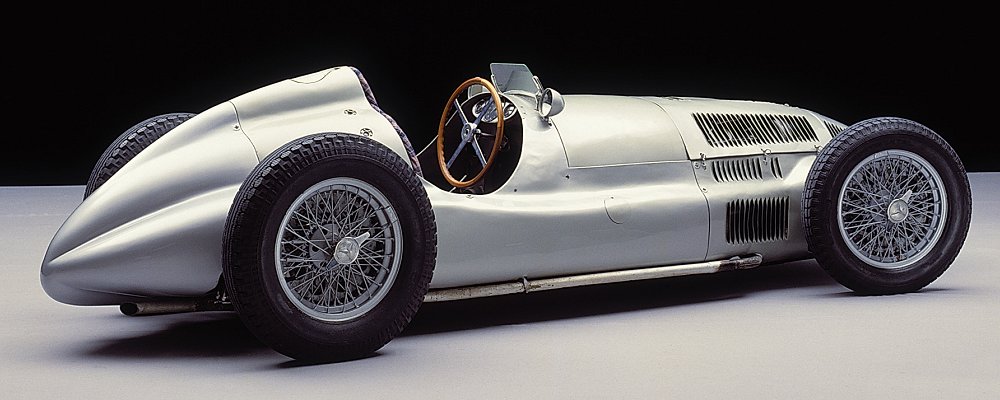

Power came from a 1.5-litre supercharged V8 engine, an advanced design that used a Roots-type supercharger to deliver exceptional output for its size. The engine produced approximately 254 horsepower at very high engine speeds, an extraordinary figure for such a small displacement in the late 1930s. The V8 configuration allowed high revs and compact packaging, while the supercharger provided strong torque and rapid acceleration. Power was transmitted through a five-speed manual gearbox, giving the driver close ratios to keep the engine within its narrow but potent power band.

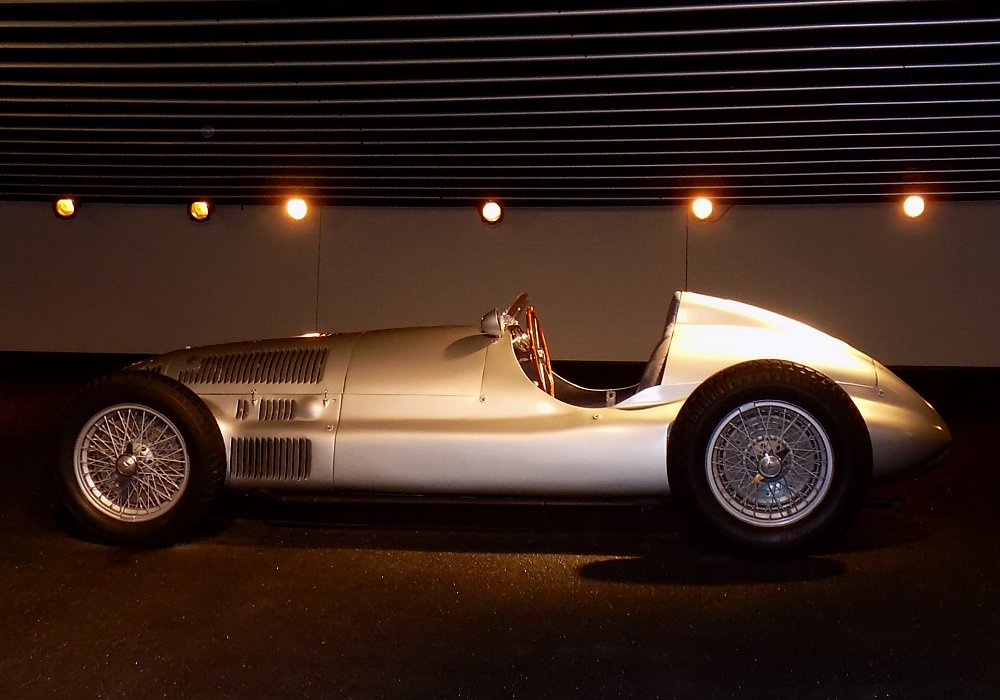

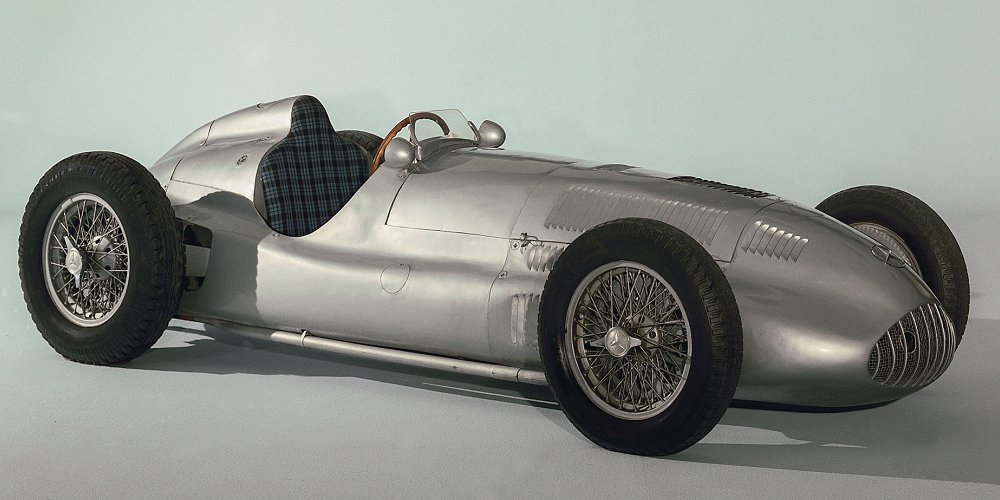

The chassis of the W165 was a lightweight tubular spaceframe, engineered to minimise mass while maintaining rigidity. Suspension featured independent front wheels with coil springs and a De Dion rear axle, a more predictable and stable solution than the swing-axle designs used on earlier Mercedes Grand Prix cars. This configuration provided improved handling and tyre contact, particularly important given the high speeds and long corners of the Tripoli circuit. Drum brakes were fitted all round, and while small compared with those on the larger Grand Prix cars, they were well matched to the W165’s lower weight.

The bodywork was compact, clean and functional, designed to minimise aerodynamic drag while allowing adequate cooling in the North African heat. Smooth aluminium panels wrapped tightly around the chassis, with exposed wheels and a low frontal area. The cockpit was narrow and tightly enclosed, placing the driver low in the car to reduce drag and improve stability. Compared with the massive W125 and W154 machines, the W165 appeared almost delicate, yet its performance was anything but.

Driving the W165 was demanding. The engine’s power delivery was intense and highly strung, requiring precise throttle control and constant attention to gear selection. The car rewarded commitment and smooth driving, and its lighter weight and improved rear suspension made it more predictable than some earlier Silver Arrows. On the fast, flowing Tripoli circuit, these characteristics proved decisive.

In its only competitive appearance, the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix, the Mercedes-Benz W165 achieved total domination. Driven by Rudolf Caracciola and Hermann Lang, the cars finished first and second, overwhelming the established voiturette competitors, particularly the Alfa Romeo teams that the regulations had been designed to favour. The victory was emphatic and left no doubt about Mercedes-Benz’s engineering capability, even under restrictive rules and extreme time pressure.

Following the Tripoli race, the W165 never competed again. With Europe on the brink of war and international motor racing effectively coming to an end later in 1939, the project was shelved. Only two W165 cars were built, making it one of the rarest Grand Prix machines ever constructed. Both survive today as priceless historical artefacts.

The Mercedes-Benz W165 1.5 Tripolis occupies a unique place in motorsport history. It was not part of a long development lineage, nor was it designed for multiple seasons of competition. Instead, it was a surgical engineering response to a specific challenge, executed with astonishing speed and precision. As such, it represents the final and perhaps most intellectually impressive achievement of the pre-war Silver Arrow era, closing that chapter of racing history with a decisive and unforgettable victory.